Hi, Everyone.

You may have noticed that I have not updated my blog in quite some time. I have been debating whether I should open up and share my personal life on this whole blogosphere because I wonder if this is the right setting. I have dedicated this blog solely to literature and done my best to limit my personal life. However, I have come to think that there may be someone out there who would benefit from me getting a little personal, at least this once.

On February 1, my father passed away. The cancer he had three years ago came back and metastasized in his bones, which was a painful and debilitating challenge. I moved into my parents' home to help take care of him in his final days, and I am so grateful I could be there for that precious time. I am writing about this because I know I'm not alone in grief, and many of you may be experiencing this in some capacity as well. Although I have no intention to go into detail with this beyond today's post, I do want to share a few things I've learned with you.

To those who are grieving:

First of all, you are not alone. For some reason, I find comfort in knowing this. I certainly don't wish that my friends would suffer loss, but I am more comfortable around the people who know how I feel. One of my good friends lost her father just three months before mine passed away, and we have clung to one another as people who get it. I hate that she lost her dad and I wish I could take away her pain, but I am grateful to have her support right now. Someone explained to me several months ago that when you lose a dearly loved one, you become part of a kind of club. It's so difficult for outsiders to know what to say or understand how you feel, but those within the club give you a knowing look and outstretched arms. I find it easier to talk to other people about their grief and their struggles because I know what to say, and I appreciate those who know what to say to me as well. I still have a long way to go, but the best way to approach it is with as much vulnerability and openness as possible. Let yourself feel the emotions that come to you and follow your heart as you restart your life.

To those whose friends are grieving:

You may have no idea what you should say and feel unable to do anything for your friend. That's ok; we don't fault you for that. We know that it's difficult for you too, and we appreciate any way you reach out. We need to be reminded that people love us in addition to the one we lost. So make time for us, and let us talk about ourselves more than we talk about you for now. Don't try to "cheer us up" because we don't want that. We want to be able to grieve around you and with you. The number one thing you can do is to just listen. But, I need to add that it is different for every person, and you should listen to the needs of your friend and not just my suggestions.

To help you, here are a few things that I personally did and did not want to hear:

1.

"Don't cry." If your friend is crying in front of you, that is because he/she feels comfortable enough to let out those feelings in your presence. If you try to soothe him/her with "don't cry," that takes it all away. If you friend is crying, let him/her cry and don't say anything about it. We need to feel safe doing it around you.

2.

"It's going to be ok." Death is the most permanent thing in the world. There is no reversing it, no way to fix it, and thus, no way for it to be "ok." Instead, we have to learn to redirect our paths and redefine our relationships in this new reality. You can't get over something like this, nor do you want to... and that's ok.

3.

"I can't imagine how you're feeling right now." This may be true, and you can certainly have these thoughts in your mind. If you say it once to your grieving friend, that's ok. But we are most comforted by those who do try to understand how we're feeling, who want to listen to our feelings and take on some of our pain with us. If you repeatedly say you can't imagine it, it feels like you don't want to try to connect with us and that may create some distance. So try to imagine what we're feeling, and we will be grateful for that.

4.

"Don't worry; you'll see him again in heaven." This is a common response, particularly from caring, religious people. You may think that this is the greatest comfort, but that may not be the case. Even if the person in grief believes in heaven, this "reassurance" is not going to change anything right now. Let us keep those thoughts to ourselves if we have them. It doesn't take away the reality of pain and feeling his/her loss now. We feel like you are dismissing our grief if you tell us this, as though we shouldn't feel sad about it now.

5.

"You made the right decision." I needed to hear this one over and over again. You can never say that too many times. There is so much insecurity that comes with loss, especially if it is sudden or of a person much too young. If your friend has had to make some big life decisions and adjust for this, assure him/her that it was the right thing to do. Encourage your friend so he/she still can feel like a strong person, despite all the feelings of weakness and powerlessness that may be overwhelming him/her.

6.

"Your dad was a great man." At a time of grief, we want it to be about the person we lost, not about ourselves. Take time to say good things about the person who has died, even if you never met that person. In that case, you can say something like, "From what I know from you, your dad was an amazing person," and that is music to our ears. Compliment the person who passed away, and do not be afraid to bring up that person in conversation. We want our loved one to continue to be a part of the conversation; it's not an off-limits name we can't handle. We want to know that he/she will be remembered.

Resources:

These were all my personal thoughts, but there are many who speak more eloquently about grief than I do. Since my audience is primarily made of avid readers, I want to include some things to read.

Blogs:

sunset soon forgotten is a young woman's journey of grief. She herself is very insightful and often includes references to other to articles I can relate to as well. She regularly says the things that I carry in my heart and wonder if other people understand.

The

"Good Grief" series is written by a theologian who recently lost his daughter. In contrast to many Christian writers, I find his words poignant and comforting. He is good about saying the things we need to hear and wish we could say to others as well.

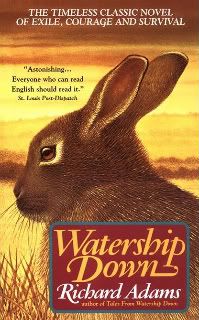

If you have been comforted by other grief blogs, please let me know and I'll include them in the list. The great thing about blogging is we can realize that we are not alone in our experiences. I am also planning to read a few books on grief at some point, so please let me know if there are any that have spoken to you in the past. So far on my list are

A Grief Observed by CS Lewis and

The Wounded Healer by Henri Nouwen.

Again, I don't intend to say more on this subject on my blog, but feel free to contact me privately if you are moved by any of this and want to talk. You can find my contact information in the left column, and I'm here if you need it.